Does Climate Change Drive Migration?

Laura Maschio

The mission statement of the United Nations (UN) Sustainable Development Goal 13 (SDG 13) is to “take urgent action to combat climate change and its impacts.” In the last decades, climate change has gradually been pushed at the forefront of public debate, thanks to the relentless environmental campaigns aimed at raising awareness on the issue. Almost simultaneously, policymakers and media sources have started depicting climate as a security issue, acknowledging the link between environmental degradation and forced displacements.

This article is the first in a series of three posts aimed at researching the impact of climate disasters on displacement, with a specific focus on the migration routes from the Sahelian region and on how they affect Europe.

The first article seeks to understand to which extent climate change leads to migration and influences migration patterns. By providing an overview of the relevant literature on the matter, it will set the stage for the deeper analysis that will be carried out in the following articles.

In the second article, the focus will be placed on the Sahel, which is defined as the semiarid region of north-central Africa stretching from Senegal eastward to Sudan, forming a transitional zone between the arid Sahara Desert in Northern Africa and the rainy savannas in the south. Through the examination of data, future projections, and good practices, it will be demonstrated how the region constitutes an interesting case study for the test of the climate-migration nexus.

Finally, in the third and last article, the European dimension will be taken into account in order to ponder on how relevant an impact climate change-induced migration has internationally as compared to its national and regional dimensions.

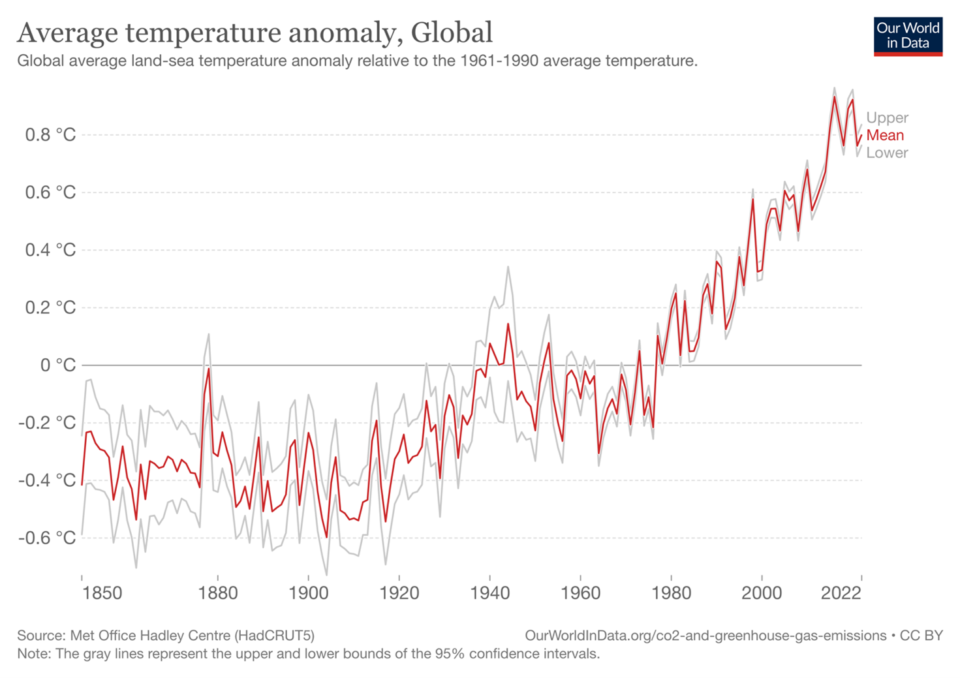

The Climate Crisis

The average global temperature has already risen 1.1ºC above the pre-industrial level, and worse still, scientists predict that it will continue to rise until 2040-2050. According to the most recent Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) Assessment Report Climate Change 2022: Impacts, Adaptation and Vulnerability, global warming, reaching 1.5°C in the near term, will not only result in multiple climate hazards in the short run, but also in significant risks to natural and human systems beyond 2040. Growing public and political awareness on the matter has contributed to the implementation of numerous climate policies based on adaptation in some 170 countries; however, considerable gaps still exist between the current adaptation measures and those actually needed to prevent or minimize the damage that climate change can cause.

Experts have long been warning about the impacts of climate change, which are most notably related to the environment – the sea level rising, the melting of glaciers, flooding and drought, among others – but that have increasingly started to be recognized as also affecting livelihoods. As a matter of fact, by the end of this decade, an estimated 700 million people will be at risk of displacement due to droughts alone. Indeed, of particular relevance for livelihoods will be changes in patterns of seasonal rainfall, which could possibly lead to a decline in agricultural productivity, food shortages, and could eventually result in increased migrations.

Displacement in a Changing Climate

Although there is no unanimous consensus on how significant climate change can be as a determining factor in the decision to migrate, forced displacement and involuntary migration from extreme weather events are now starting to be addressed, given the considerable number of people affected by the problem.

Data from the Internal Displacement Monitoring Centre (IDMC) show how in 2021 alone, an estimated 22.3 million internal displacements were caused by weather-related disasters.[2] As a matter of fact, the existing literature points out how environmental migrants are more likely to move within national borders than they are to migrate abroad [3], oftentimes from rural to urban areas. Irrespective of the type of migration, what is sure is that climate change is likely to increase the intensity of weather-related hazards, thus driving displacements risks.

While every region is likely to be impacted by climate change, the vulnerability of ecosystems and people differs substantially depending on the context: according to the IPCC Report, approximately 3.3 to 3.6 billion people live in regions that are considered highly vulnerable to climate change. In particular, the IPCC states that “vulnerability is higher in locations with poverty, governance challenges and limited access to basic services and resources, violent conflict and high level of climate-sensitive livelihoods.” Global hotspots of high human vulnerability are found, inter alia, in West-, Central- and East Africa, thus including the area referred to as Sahel.

Overall, climate change is expected to have significant impacts on human mobility patterns in the coming decades, in particular when intersecting with other drivers of migration such as conflict, poverty, and political instability. As will be thoroughly explained in the next post, the Sahel is indeed a region where people are significantly susceptible to environmental conditions, that are expected to drive displacement and migration both in the short and the long term.

[1] Hannah Ritchie, Max Roser and Pablo Rosado (2017) – “CO2 and Greenhouse Gas Emissions”. Published online at OurWorldInData.org. Retrieved from https://ourworldindata.org/grapher/temperature-anomaly.

[2] See: https://www.internal-displacement.org/database/displacement-data. Figures are likely to be an underestimation of the actual number of IDPs.

[3] See, for example: Kate Burrows and Patrick L. Kinney, “Exploring the Climate Change, Migration and Conflict Nexus”, in International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, Vol. 13, No. 4 (April 2016), p. 1-17, https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph13040443.