Climate Mobility in the Sahel

Laura Maschio

via Unsplash / Annie Spratt

As has been thoroughly explained before, climate change can act as a multiplier of threats, exacerbating existing vulnerabilities and making it difficult for people to survive where they are. In order to fully grasp the potential for massive climate migration in the Sahel, it is first and foremost necessary to understand the long history of migration in West Africa.

Migration as a Strategy for Survival and Security

Migration is indeed extremely common in the region, where many people live as semi-nomads, farming and feeding cattle in the north during the rainy season and moving towards the wetter south to find better grazing lands during the dry season.[1] Seasonal nomadism has been an essential strategy for surviving in the fragile Sahelian ecosystem, enabling a population of 4-5 million individuals to cope with the frequent climatic crises that occur in the region.[2] Therefore, while the Western public opinion usually associates migratory flows with a threat to security, the Sahelians generally see migration as an opportunity for greater security and a key strategy to overcome food and environmental insecurities caused by the frequent natural disasters.

Historically, the prevailing pattern of intra-regional migration in West Africa was that of a southward movement towards coastal states: Ivory Coast remained the only destination throughout the 1980s and the 1990s, while from the 90s onwards the civil war and the economic decline of the country brought about the rising importance of Libya, eventually paving the way for the increase in West African migration to Europe.[3]

However, notwithstanding the alarmist narrative of an invasion of Europe by Sahelians crossing the Sahara, evidence shows how the majority of Sahelian migrants actually move within the region instead of heading for Europe: in 2020, only 15 percent of the total emigrants from Western Africa emigrated to the EU, while the overwhelming majority of migrants remained in the region, with Ivory Coast, Nigeria and Burkina Faso as the main immigration poles. Likewise, people who were forced to leave their homes due to conflicts and natural disasters mainly remained in the region, with just a small percentage of the overall number of displaced people moving to the EU.[4]

via Unsplash / Annie Spratt

Possible Scenarios for Future Displacement

Given the above, it is possible to assert that in the Sahel, unlike what can be said about other regions, a positive association between climate change and net-migration exists. This is mainly due to the long-standing migration processes in the region in face of the recurrent climate extremes resulting in food insecurities.

If this assumption is true, a mass migration from the Sahel, one of the most climate-vulnerable regions of the planet, can be expected. On top of that, Africa’s pastoral areas are predicted to see a net outward movement of people of around 4 million by 2050 as a result of climate impacts, while coastal areas could lose up to 2.5 million people as a result of sea level rise and other climate stressors.[5]

However, it is necessary to underline that not everyone who wants to move have the resources to do so: moving requires financial means and social connections, or it may seem too risky, due to a perceived lack of physical security or opportunities. This translates into a substantial risk for the most vulnerable groups and individuals, who could become trapped as a result of being too poor, old, or sick to migrate. On the other hand, not everyone wants to move when climatic conditions get worse: some people may feel rooted to their land to the point that they prefer not to leave despite the threats they may face. This is particularly true for the old generation, while young Africans are more likely to consider moving: two out of every five African youth see mobility as normal or even aspirational, and almost one in five have concrete plans to leave.[6]

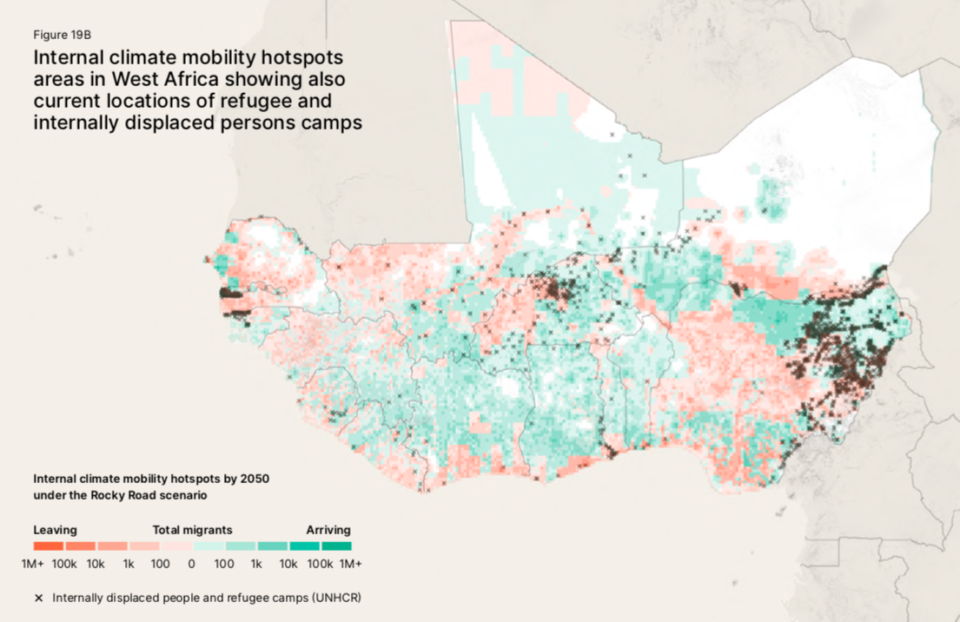

Whether willingly or not, the ever-worsening climate conditions will force more and more Sahelian people to leave their communities. The Africa Climate Mobility Initiative (ACMI) developed two models to simulate different potential futures for climate mobility in Africa, one envisaging a high emissions and inequitable development scenario (Rocky Road) and another where high emissions are complemented by an inclusive development scenario (High Road). Under the worst-case scenario, internal climate mobility in Africa could reach up to 113 million people by 2050, with West Africa being one of the hotspot areas.

Source: ACMI Africa Climate Mobility Model, 2022

Being Africa the least responsible continent to global greenhouse emissions but the most vulnerable to the negative impacts of climate change, a collective effort to stem global warming and keep it within the UN-set limit of 1.5ºC is necessary. Moreover, to prevent the most vulnerable from being trapped in a fragile and deteriorating ecosystem, mobility should be embraced as an effective adaptation strategy, and regional and trans-Saharan migratory flows should be regulated and supported in regional and international policies.

[1] C. Samimi, M. Brandt, “Environment and Migration in the Sahel”, in D. Hummel, M. Doevenspeck, C. Samimi (eds.), Climate Change, Environment and Migration in the Sahel, micle working paper no. 1, Frankfurt/Main, 2012.

[2] See, for example: M. Aime, A. De Georgio, Il grande gioco del Sahel, Torino, Bollati Boringhieri, 2021.

[3] M. Doevenspeck, “Migration in West African Sahel”, in D. Hummel, M. Doevenspeck, C. Samimi (eds.), Climate Change, Environment and Migration in the Sahel, micle working paper no. 1, Frankfurt/Main, 2012.

[4] Data retrieved from the European Commission’s Atlas of Migration, available at https://migration-demography-tools.jrc.ec.europa.eu/atlas-migration/country-profiles?selection=AFR_W.

[5] Africa Climate Mobility Initiative, African Shifts: The Africa Climate Mobility Report, Addressing Climate-Forced Migration and Displacement, available at https://africa.climatemobility.org/.

[6] Ibid.